Mathematical Mayhem: The “Crime Wave” Continues

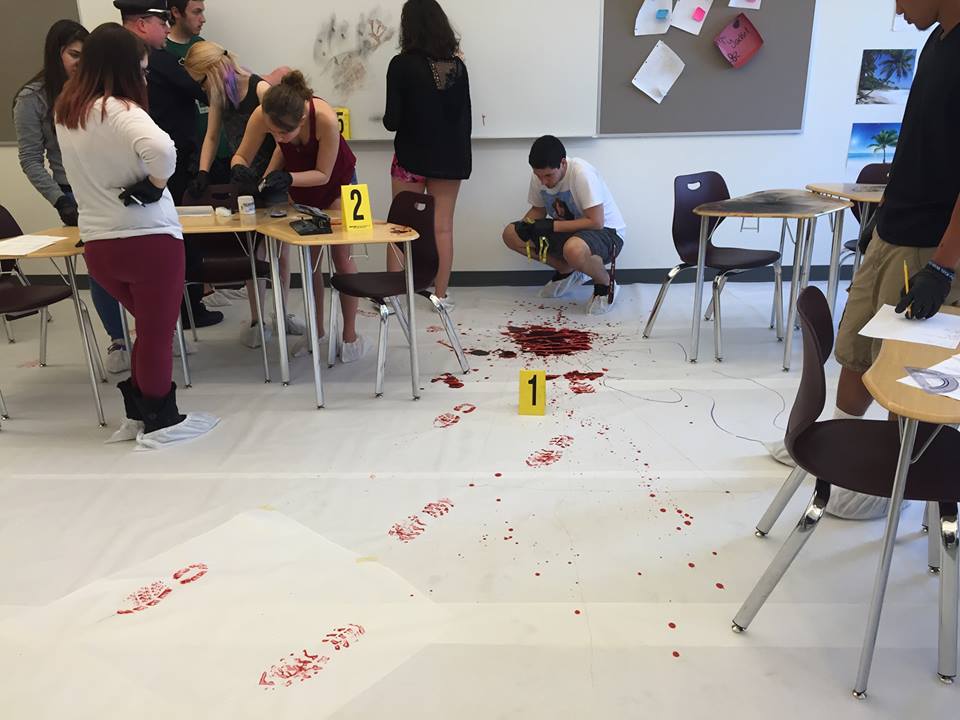

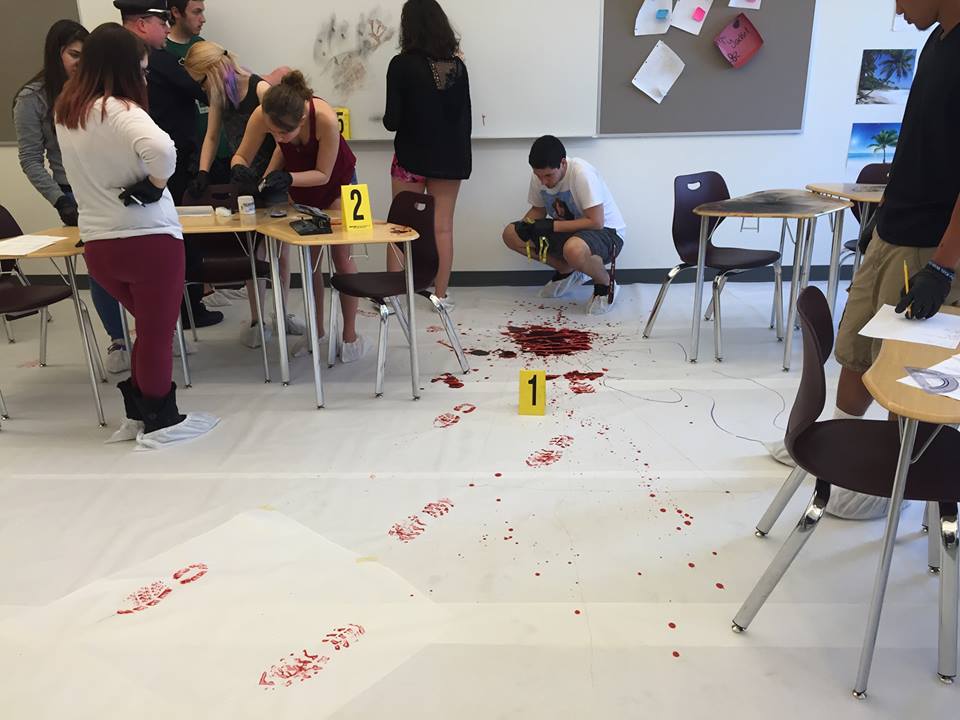

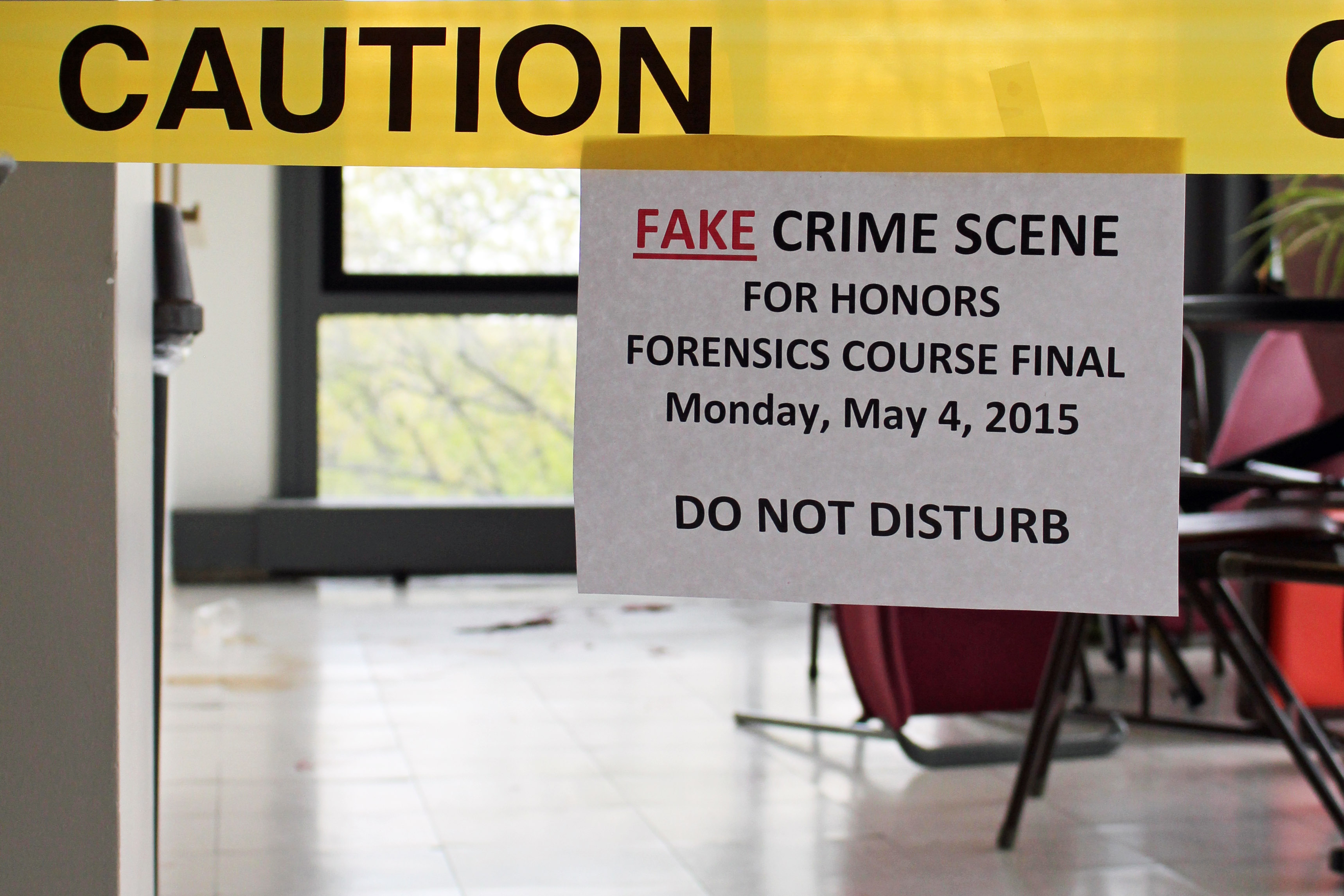

[July, 2015] On May 4, 2015, DIMACS Associate Director Eugene

Fiorini  was a

central figure in what turned out to be a multi-state “crime wave.”

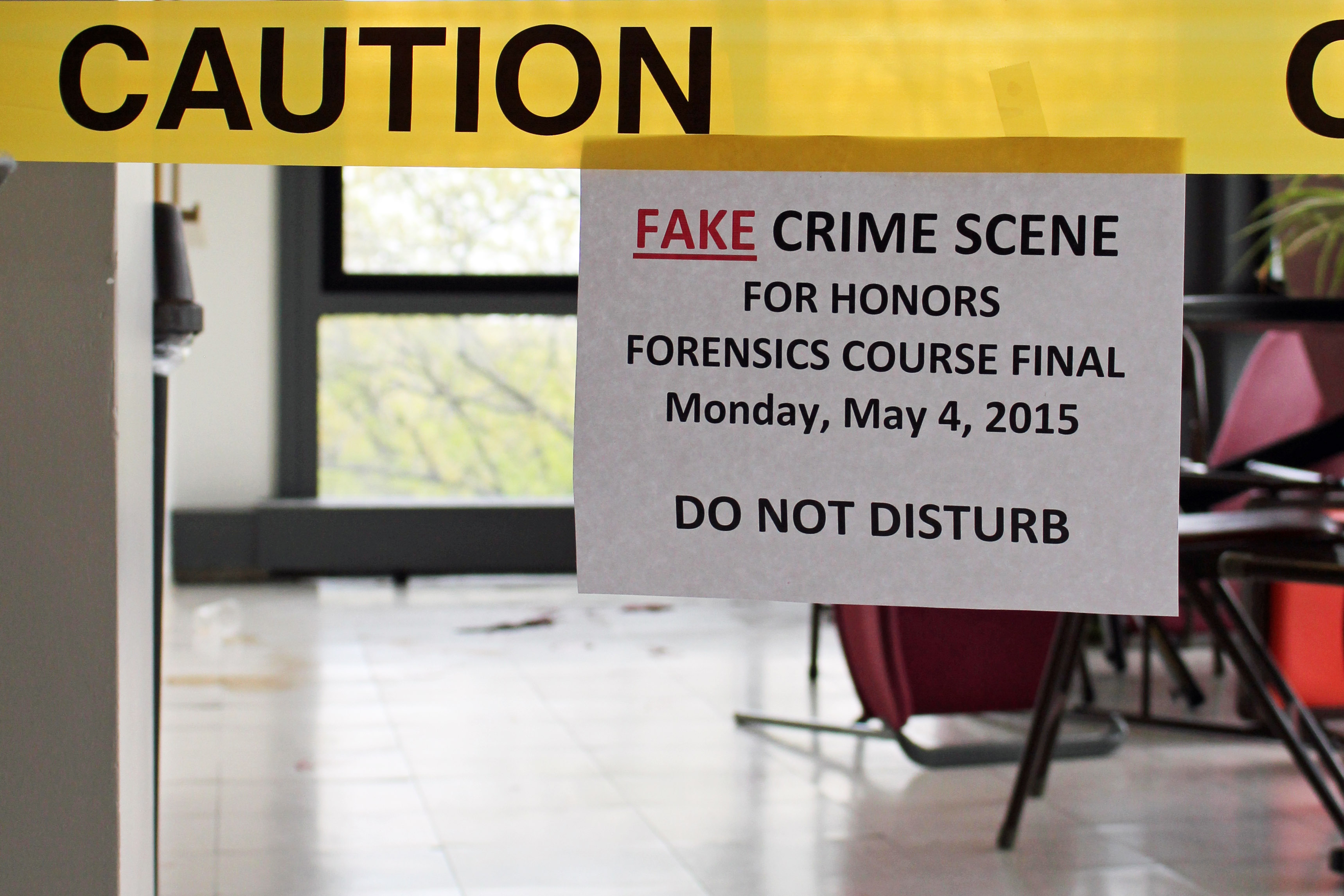

The “crimes” were completely staged, but they were serious business

for students participating in two different classes on mathematical

forensics.

was a

central figure in what turned out to be a multi-state “crime wave.”

The “crimes” were completely staged, but they were serious business

for students participating in two different classes on mathematical

forensics.

In Ayer, MA, high school teacher Jessie Yackel worked with Detective

Andrew Kularski of the Ayer Police Department to teach her students

the mathematics behind crime scene investigations. Meanwhile, in

Piscataway, NJ, Fiorini was doing the same thing with his honors

seminar at Rutgers. Both classes ended on May 4 with students

conducting investigations into the untimely (unsubstantiated and

completely untrue) demise of unpopular faculty members. Fiorini

taught a course

in 2013 that also ended with a tale of murder and deceit in

service of teaching mathematical forensics.  Evidence

suggests that he was at it again.

Evidence

suggests that he was at it again.

Mathematical forensics is the application of mathematics in forensic

science, which, broadly speaking, is the application of scientific

methods to gather and analyze evidence for use in a court of law. It

turns out that forensic science is fertile territory for

mathematical analysis. Basic statistical principles are used in

computing body size and gender from measurement of bone fragments or

stride length. Time of death estimates can make use of simple

algebraic calculations to estimate body temperature over time or can

employ more sophisticated methods that apply differential equations

based on Newton’s Law of Cooling. Trigonometry and vector analysis

are the central tools of blood spatter and ballistic evidence

analysis. They help to determine the position of the victim and

assailant at the time an attack occurred.

Because of popular television shows like CSI: Crime Scene

Investigation many of these  techniques

are already familiar and interesting to students. Most students

readily relate to the search for fingerprint matches to a national

database, but until they take Fiorini’s class, they probably don’t

know that graph theory is applicable to fingerprint analysis.

Fingerprints formed by the ridge patterns on fingertips are unique

to each individual, making their identification a workhorse in

criminal forensics. A coarse classification based on prominent ridge

features allows investigators to winnow the database to a smaller

set of

techniques

are already familiar and interesting to students. Most students

readily relate to the search for fingerprint matches to a national

database, but until they take Fiorini’s class, they probably don’t

know that graph theory is applicable to fingerprint analysis.

Fingerprints formed by the ridge patterns on fingertips are unique

to each individual, making their identification a workhorse in

criminal forensics. A coarse classification based on prominent ridge

features allows investigators to winnow the database to a smaller

set of  candidate

matches, but it is not enough to make a definite match. To confirm a

match they have to rely on a detailed analysis of finer

characteristics within the ridge patterns. Fiorini applies concepts

from graph theory to identify such characteristics and the relations

between them in a “module”

on fingerprint analysis that he coauthored as part of the

DIMACS project on the Integration

of Mathematics and Biology. The module is one of 20 modules in

mathematical biology that have been developed through DIMACS

projects for use in high school mathematics and science classrooms.

candidate

matches, but it is not enough to make a definite match. To confirm a

match they have to rely on a detailed analysis of finer

characteristics within the ridge patterns. Fiorini applies concepts

from graph theory to identify such characteristics and the relations

between them in a “module”

on fingerprint analysis that he coauthored as part of the

DIMACS project on the Integration

of Mathematics and Biology. The module is one of 20 modules in

mathematical biology that have been developed through DIMACS

projects for use in high school mathematics and science classrooms.

More recently, Fiorini has developed another module on blood spatter

analysis and time-of-death calculation. The modules are part of a

growing portfolio of activities and materials in mathematical

forensics that Fiorini has been building and sharing with teachers.

In so doing, he has inspired teachers, like Jessie Yackel at

Ayer-Shirley High School, to bring the topic to their students.

Violeta Vasilevska, a professor of mathematics at Utah Valley

University (UVU), is also helping to spread the word about

mathematical forensics following an encounter with Fiorini.

Vasilevska attended the 2014 Reconnect

Workshop on Forensics in which Fiorini was the primary

speaker. Inspired by the topic, she and her colleagues organized a

conference, “Math and

Forensics: Whodunit, Howdunit, Whendunit,” for high school

students and teachers held at UVU in May 2015. With 150 registered

participants, the conference illustrates the enthusiasm for the

topic.

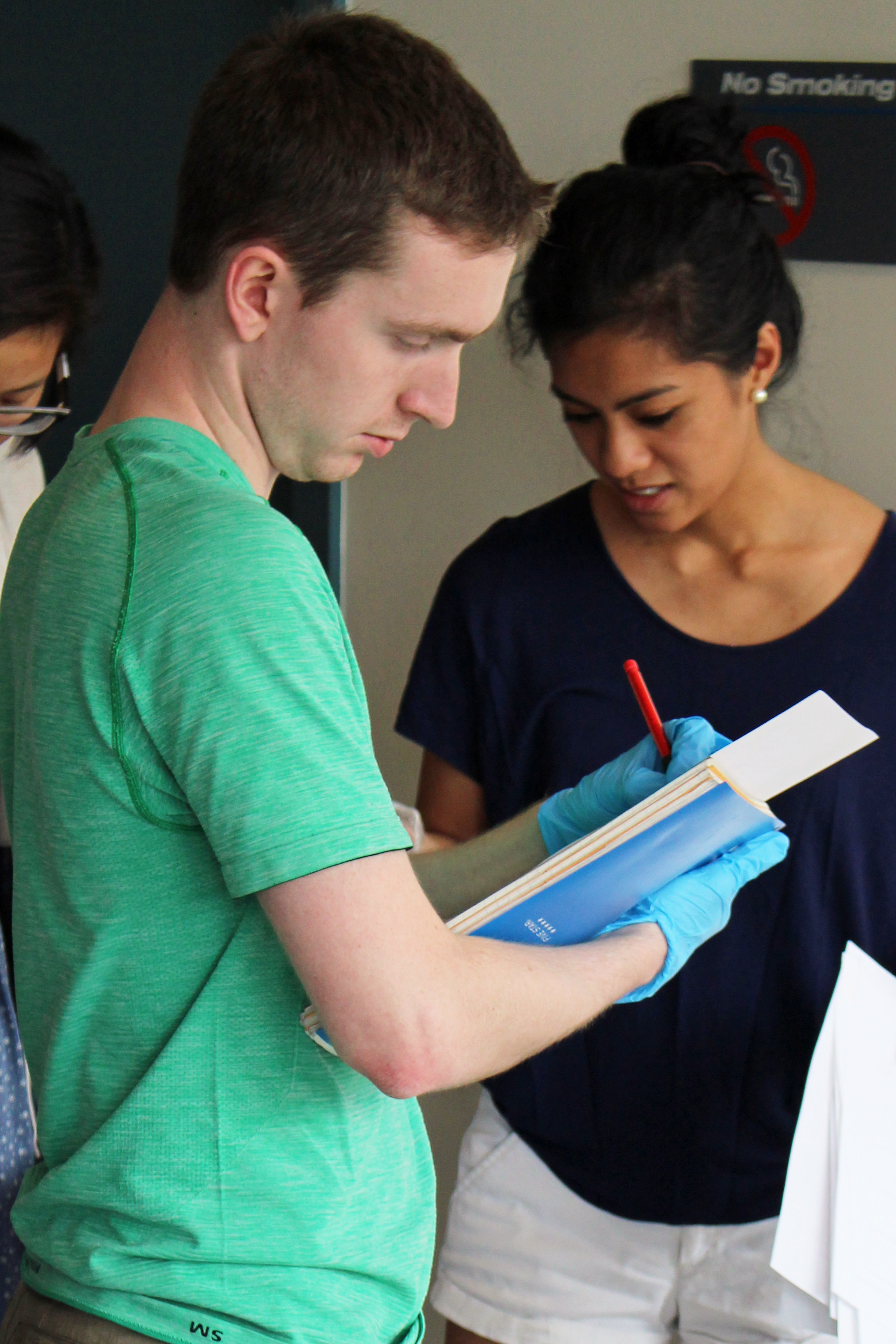

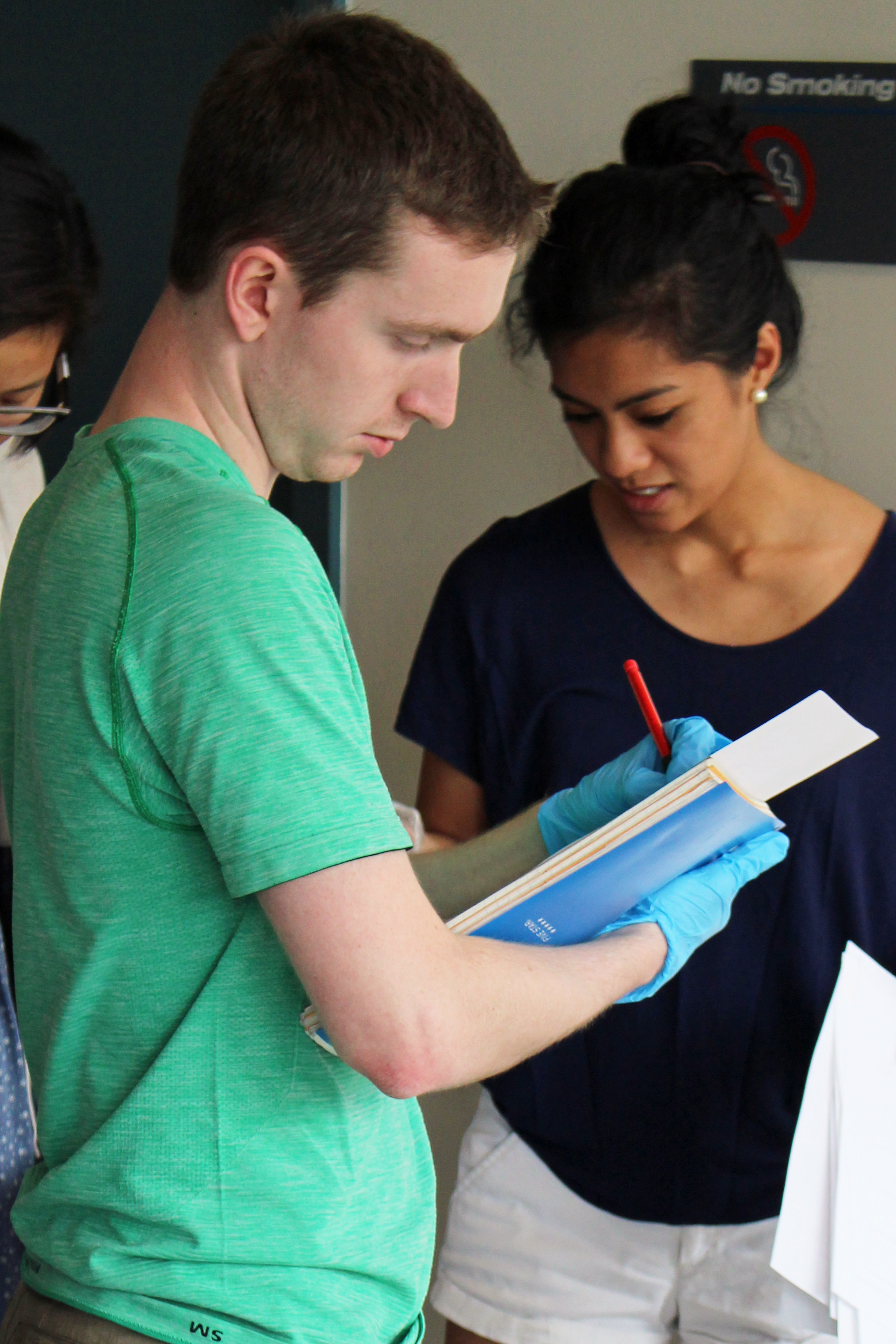

Fiorini’s students are not the only ones to be immersed in the

murder-mystery drama of his final exams.  DIMACS staff have

contributed to the “script”, the fingerprint database, the suspect

pool, and alas, played the victim – all in service of education.

DIMACS staff have

contributed to the “script”, the fingerprint database, the suspect

pool, and alas, played the victim – all in service of education.

The crime wave at DIMACS will likely end soon, and the students may

have played a role. At the end of the summer, Fiorini will step down

as DIMACS Associate Director to return to the classroom. He will

join Muhlenberg College as a Professor of Mathematics, where he will

inspire students and (most likely) launch future waves of crime and

mathematical mayhem. All of us at DIMACS wish him well in this new

endeavor and thank him for all he has done during his time at

DIMACS. We will miss having him here at DIMACS full-time, but we

look forward to continuing to work with him as an active DIMACS

member in his new role!

Printable version of this story: [PDF]

DIMACS Homepage

DIMACS Homepage

Contacting the

Center

was a

central figure in what turned out to be a multi-state “crime wave.”

The “crimes” were completely staged, but they were serious business

for students participating in two different classes on mathematical

forensics.

was a

central figure in what turned out to be a multi-state “crime wave.”

The “crimes” were completely staged, but they were serious business

for students participating in two different classes on mathematical

forensics.  Evidence

suggests that he was at it again.

Evidence

suggests that he was at it again.  techniques

are already familiar and interesting to students. Most students

readily relate to the search for fingerprint matches to a national

database, but until they take Fiorini’s class, they probably don’t

know that graph theory is applicable to fingerprint analysis.

Fingerprints formed by the ridge patterns on fingertips are unique

to each individual, making their identification a workhorse in

criminal forensics. A coarse classification based on prominent ridge

features allows investigators to winnow the database to a smaller

set of

techniques

are already familiar and interesting to students. Most students

readily relate to the search for fingerprint matches to a national

database, but until they take Fiorini’s class, they probably don’t

know that graph theory is applicable to fingerprint analysis.

Fingerprints formed by the ridge patterns on fingertips are unique

to each individual, making their identification a workhorse in

criminal forensics. A coarse classification based on prominent ridge

features allows investigators to winnow the database to a smaller

set of  candidate

matches, but it is not enough to make a definite match. To confirm a

match they have to rely on a detailed analysis of finer

characteristics within the ridge patterns. Fiorini applies concepts

from graph theory to identify such characteristics and the relations

between them in a “module”

on fingerprint analysis that he coauthored as part of the

DIMACS project on the Integration

of Mathematics and Biology. The module is one of 20 modules in

mathematical biology that have been developed through DIMACS

projects for use in high school mathematics and science classrooms.

candidate

matches, but it is not enough to make a definite match. To confirm a

match they have to rely on a detailed analysis of finer

characteristics within the ridge patterns. Fiorini applies concepts

from graph theory to identify such characteristics and the relations

between them in a “module”

on fingerprint analysis that he coauthored as part of the

DIMACS project on the Integration

of Mathematics and Biology. The module is one of 20 modules in

mathematical biology that have been developed through DIMACS

projects for use in high school mathematics and science classrooms.

DIMACS staff have

contributed to the “script”, the fingerprint database, the suspect

pool, and alas, played the victim – all in service of education.

DIMACS staff have

contributed to the “script”, the fingerprint database, the suspect

pool, and alas, played the victim – all in service of education.